By: Joe Garcia

As the American-born son of Cuban exiles, I would like nothing more than for my mother and father to be able to return to their country one day. I also wish for my daughter to experience the wonders of the land where her grandparents met and grew up, and for her, along with all of your children and future generations, to be able to travel and live throughout a western hemisphere that is free of the violence and economic disparities that haunt it today. In order to accomplish this worthy objective, a new approach to US policy toward Cuba and Latin America is needed, which the Obama administration has already begun to unveil.

When I became Executive Director of the Cuban American National Foundation nearly ten years ago, one of my main goals was to shift the focus of the debate over US-Cuba policy from Fidel Castro to the Cuban people. As we accomplished this goal, we helped create a moderate majority within the Cuban-American community that believes it is time to cast aside outdated arguments from the Cold War, and focus instead on achieving tangible results. In Washington, we were able to formulate a working consensus among lawmakers from both sides of the aisle that change in Cuba must come from within and that our efforts should therefore focus on fostering a civil society within the island. However, nearly a decade after I took the helm of the largest Cuban exile group, another paradigm shift is sorely needed to address the following unresolved matters: what the policy of the United States toward Cuba should be going forward and how it fits within the broader partnership we seek with the Americas.

To answer the former, we must first recognize that the embargo alone is not an effective policy to promote democracy in Cuba. The proof is in the pudding, as half a century has demonstrated well beyond a reasonable doubt the need for other measures. But our efforts should not focus solely on engaging in a trite debate over whether we should maintain or lift the five-decade-old embargo – falling victim to this “either-or” fallacy would be a great disservice to Cuba’s political prisoners, the nearly two million Cubans living in exile, and the region as a whole. Instead, an honest and open assessment is needed to identify better policy alternatives.

In order to turn the page on the debates of the past and embrace a new and effective approach, we must accept a series of truths and recognize the possibilities that lie ahead. Those who stubbornly adhere to the status-quo must have the courage to recognize the unequivocal shortcomings of our current policy and that the embargo itself is not the end, but that a democratic Cuba where human rights are respected is, and that such a noble common purpose cannot be the prisoner of a rigid ideology. Meanwhile, those who insist that the immediate, unilateral lifting of the embargo will spawn democracy on the island “simply because it hasn’t worked for fifty years,” must entertain the notion that in the absence of Fidel Castro, the embargo may serve as leverage for democratic reform on the island.

Yet our policy toward Cuba cannot be formulated in a vacuum while we neglect a comprehensive approach to the Americas. Far too often the United States has dealt with other Latin American nations through the prism of Cuba, or worse, without any concerted strategy at all. The results have been disastrous for both the people of the Americas and the interests of the United States. At the time of writing, a significant number of Latin American nations has been over-taken by left-wing populist autocrats, who may have been democratically elected, but whose governing style is anything but democratic. Their rise to power has often featured invocations of the troubled relations between the United States and Cuba, as is the case in Venezuela. This comes after decades of corrupt, right-wing paramilitary regimes in the region, which were often-times supported by previous American administrations in an attempt to halt the spread of Soviet communism.

The Cold War has ended, and our policies should reflect this reality. To break from the past and chart a new course in Latin America, the United States must implement a broader strategy that addresses the common threats posed by violence, failed economies and drugs; advances our mutual interests for peace, progress and prosperity; and is based on the core values shared by all people throughout this hemisphere. To that end, President Obama acted prudently this weekend by allotting the issue of Cuba its appropriate role at the Summit of the Americas without allowing it to dominate all discussions or hinder the meaningful work the United States must do with respect to other nations. In addition, the lifting of the counter-productive Bush/Diaz-Balart restrictions that limited the ability of Cuban-Americans to help their families was also a positive indication of the new president’s principled, forward-thinking approach to foreign policy.

Perhaps this new approach is why I am optimistic that the Obama administration may very well help bring about the much-needed paradigm shift described above. It can also be why so many, myself included, are hopeful about the future as the White House continues to roll out its policy agenda concerning Cuba and the rest of Latin America.

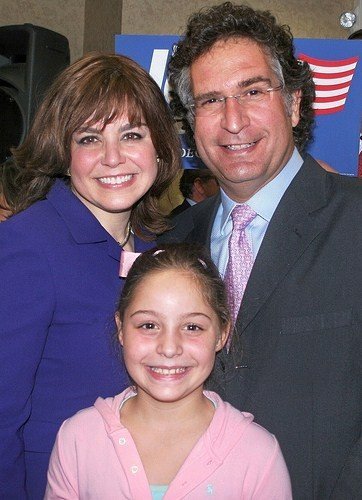

Joe Garcia is the former Executive Director of the Cuban American National Foundation and Chairman of the Florida Public Service Commission. He currently lives in Miami with his wife, Aileen, and daughter Gabriela.

Joe,

I totally agree with you. My grandfather and my wife came to this country as refugees. My children are descendents of ‘mambises” who fought against Spain for Cuban independence. It is time for the United States to engage Cuba in a different way so that your children and mine can visit the land of their ancestors, pay tribute at the graves of their forbears and connect with the land that Columbus called the most beautiful on Earth. Thank you for the great job you do in defending your position against “la vieja guardia” on shows like Maria Elvira Live. It is time that people see that Cubans living outside the island don’t all share the opinions of the some Miami exiles who haven’t been on the island in almost half a century.