A poll by the Associated Press and Univision shows the language and cultural barriers continue to exist as Hispanic enrollment climbs in schools across the country.

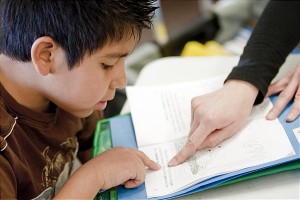

According to the study, in Spanish-speaking homes, parents find it a challenge to help their children with their homework and have difficulties communicating with teachers. At the schools, Spanish-speaking students struggle in English-immersion classes.

“The language barrier is still a serious risk factor for Hispanics,” said Michael Kirst, a Stanford University professor emeritus of education who helped analyze the survey.

Even though a majority of Hispanics value higher education, 87% to be exact, only 13 % actually have a college degree.

Kirst says that “the odds of completing high school, and particularly college, significantly drops.” even with many schools replacing Spanish with English in classrooms, for a student evaluated as English learners.

The National Opinion Research Center conducted the poll from March 11 to June 3. A total of 1,521 Hispanics were interviewed in English and Spanish via mail, telephone, and the internet.

Among the findings was that 78% of Hispanics had children enrolled in K-12 classes that were taught mostly in English, with only 3% in Spanish. Only 20% of dominantly Spanish-speaking parents say they were able to communicate “extremely well” with their child’s school in comparison to the 35% of Hispanics who speak English fluently who said they could.

About 42% of the dominant Spanish-speaking parents said it was easy for them to help with their children’s homework compared to 59% of the English-speaking parents. This could be a contributing factor why children in dominantly Spanish-speaking homes are less likely to seek help with homework from their parents. While 80% of students in mainly English-speaking homes sought their parents for help, only 57% in Spanish-speaking homes did the same.

An investment of $50 million next year to promote English learning by the Department of Education could help alleviate this issue next year. The money will be used in part to fund research and development of “dual-language immersion,” a bilingual approach gaining favor among many linguists.

The idea of dual-immersion does not sit will with many in some parts of the country. In California, Arizona and Massachusetts voters have largely banned bilingual classes. An estimated 30 states and numerous localities have made English the official language by law, a move that critics say will lead to more cuts in bilingual programs.

The Supreme Court sided with Arizona last year in a 5-4 vote saying the federal government should not supervise the state’s spending for teaching students who don’t speak English.

Federal law, however, mandates that if the parents’ English is limited then schools must provide notices and information about student activities in a language they can understand. Some school districts are under review by the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights to see if students are being denied a fair education.

Roxana Montoya, a parent in Miami learning English, says she struggles to help her 12 year-old son with school work. “He’d get out at 3 and at 9, we still wouldn’t be done with the homework,” she said.

Spanish speaking students should receive help so they don’t fall behind. I think transitioning to a dominantly English speaking classroom should be the goal but we shouldn’t set these students up for failure by immersing them in English only classrooms when they don’t fully grasp the language just yet.